The railroad came to Stillwell in the 1890s. Although Historic Effingham Society has known of a depot in Stillwell, these are the first photographs of the depots in Stillwell that we have found.

The depot sat on the west side of the railroad, on the same side as the old post office, some 50 or more feet from the current Stillwell railroad crossing on Stillwell-Clyo Road. The larger depot in the accompanying photo was the first one and a small white building was the second. No one I spoke with knows why the first depot was replaced but fire is a likely possibility.

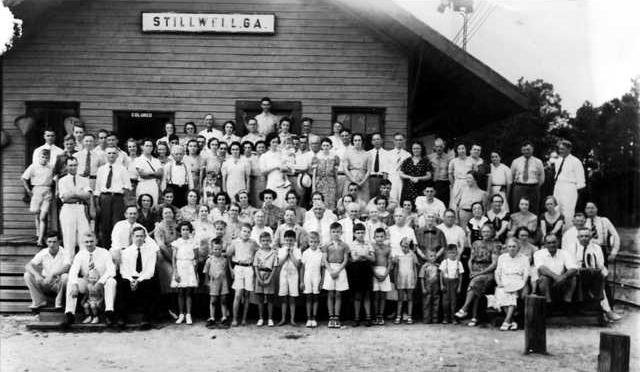

The depot photo with people shows the tracks, mailbag and signage on the south end of the depot. This was the first and larger of two depots, according to what Ralph Gnann had been told by his father. Beginning in the 1890s, railroads were forced by Southern states to maintain separation of the races in stations and passenger cars. On Nov. 25, 1955, the Interstate Commerce Commission banned segregation on buses, trains and in railroad stations. It took several years until this was implemented and bus stations were the last to comply with desegregation.

Those posed for the accompanying photograph were in Stillwell for the Bird family reunion. Likely according to some of the Bird Family descendents, the reunion was held at Madge Mingledorff Wilson’s home very near the railroad. The Bird family, with many children, lived on Stillwell Road in the vicinity of the home of the late Henry Webb and held annual reunions.

Lena Ruth Nizzi, Earl Shearouse and Ralph Gnann remember the second, smaller depot. Alice Rhoda G. Ferrell recalls boarding the train back and forth from the depot while attending college in Newberry, S.C.

The daily newspapers were delivered by train in a bundle tied with wire. On Sundays the papers were thrown out with no stop at the depot. Occasionally the papers were late.

The first subscriber picked up the bundle and left the Sunday papers on the bench at the depot for the others to pick up. Ralph Gnann recalls the papers being late and having to be picked up on the way home from Grace Lutheran Church. His family stopped to get their paper but the bundle had been sucked under the train and shredded into small pieces. Ralph was heartbroken to miss the comics that he dearly loved.

According to C. B. (Major) Gnann Jr., from the 1890s, when depots were built, they were manned 24 hours a day. Communication was by Morse code. Operators were hired and had to find a place to live. Major’s grandparents offered room and board at $1 a day which included three meals. Major’s aunt Ethel Gnann was one of the operators. She graduated from the Telegraphy Southeastern Railroad College in Atlanta.

When Major’s parents married, they lived with his father’s parents and talked about the fun they had with the operators staying there. They sang, played games and did other things. Albert Gnann inherited a cookbook given to his grandmother Lena Exley Gnann, signed by the depot agent’s wife.

The depot early on was used to ship crops and produce. Barrels were shipped by a local barrel manufacturer. Cane syrup was made and packed in cans, then transported for sale by rail. The high platform on the depot allowed for the loading and unloading of cargo.

Somewhere after World War II the depot was no longer manned. Technology and the way communications were conducted changed for the railroad. The second depot, which was a much smaller building, became dilapidated after it was no longer used. The building had seen much brighter, prosperous days that are now gone forever.

This was written by Susan Exley of Historic Effingham Society. If you have photos, comments or information to share, contact her at 754-6681 or email her at: hesheraldexley@aol.com.