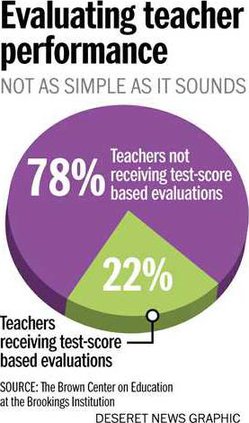

Just over a decade ago, improving teacher quality meant stacking up paper credentials. President George W. Bush's signature No Child Left Behind program, for example, created incentives for schools to hire more teachers with post-secondary education or certification in subject areas.In the Obama years, the tide has shifted, notes a new study released by the Brookings Institution. Teachers are increasingly being paid, measured and promoted on the basis of classroom performance rather than credentials.And yet, the report argues, far too little is known about whether these teacher evaluation systems are telling us what we really need to know.In "Evaluating Teachers with Classroom Observations," researchers at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution released their conclusions Tuesday, drawing from studying multiple years of data from four major urban school districts.Overall, the Brookings report offered hard evidence that merit-based teaching evaluations, though imperfect, are statistically valid and much more valuable than older measures using paper credentials.

Are teacher evaluations telling us what we need to know?

Latest

-

Its toxic: New study says blue light from tech devices can speed up blindness

Its toxic: New study says blue light from tech devices can speed up blindness -

This upset man was turned away from voting polls because he was wearing a MAGA hat; here's what th

This upset man was turned away from voting polls because he was wearing a MAGA hat; here's what th -

Facebooks stock suffers the worst single-day market loss in history. Heres how much Mark Zuckerber

Facebooks stock suffers the worst single-day market loss in history. Heres how much Mark Zuckerber -

Roseanne Barr speaks with Sean Hannity in first TV interview since racist tweet controversy. Here ar

Roseanne Barr speaks with Sean Hannity in first TV interview since racist tweet controversy. Here ar