What if the solution to homelessness was simply giving people a place to live?

A massive five-year pilot project in Canada called At Home/Chez Soi used the "housing first" approach to battling homelessness, and the results are in.

More than 2,000 homeless people diagnosed with mental illness have remained in stable housing situations over a two-year period when placed in clean, renovated apartments and provided support services for things like substance abuse and mental illness.

Often people who are chronically homeless have hurdles like addiction or mental health issues, said Catharine Hume, director of the pilot program at the Mental Health Commission of Canada, and those things "don't magically stop with housing," she said.

But housing gives them the security and stability to move ahead. "They can start to think about other things, like 'What do I want to do with my life?' 'Do I want to go to school?' 'Do I want to volunteer?' A home opens up a sense of hopefulness and possibility."

A clean, well-lighted place

Traditional help for the homeless centers around underlying issues first — an applicant might go to a shelter; and if they show good behavior there, they might get bumped up to a group home, depending on if they are deemed "housing ready" by showing progress with things like substance abuse problems, mental health issues or budgeting.

This "steps" method just doesn't work for some populations, said Julian Somers, professor at Simon Fraser University and the lead researcher on the Vancouver study of At Home/Chez Soi project.

"We know from research that certain populations in shelters have enough going for them that they can move on, but there is a subset that need something uncommon and deliberate," said Somers. Factors like being raised in foster care, having difficulty in school, mental illness and other "external hardships" make it hard for some people to get on their feet.

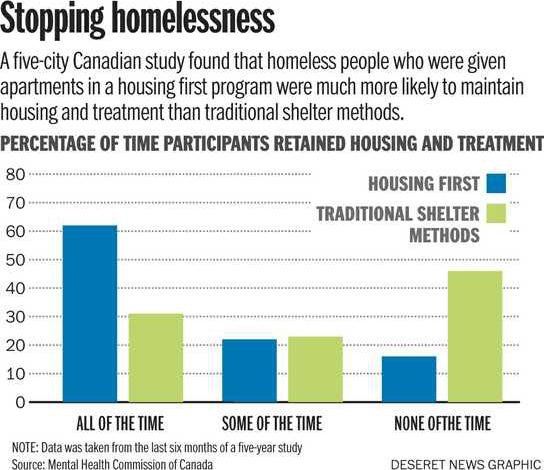

The five-city study tested the housing first group against a control group that received the traditional "steps" and shelter approach, and those in housing first retained housing and treatment in much higher rates. In the last six months of the study, only 16 percent of housing first participants were back on the streets, compared to 46 percent from the traditional "steps" method control group.

Shelters are not always safe and secure, said Hume, who points out that they are often vermin-infested and rife with crime. "Stuff gets stolen, people fight, sometimes you're sleeping on a mat on the floor; it's pretty unpleasant."

Offering pleasant housing provides stability and is generally met with enthusiasm. She says that people approached for her program almost never turned it down.

"Generally, people want to have a place to live. There's an assumption that people choose that lifestyle — but that's silly when you think about how difficult those lives are. Almost nobody referred to our project chose not to enter or try."

Pilot programs

Cities like Milwaukee and Salt Lake City have had similar success with providing homeless people clean, renovated apartments and providing support services for things like substance abuse and mental health. Salt Lake City's programhas reduced its chronic homeless population to less than 4 percent — which is a statistical zero.

When Salt Lake began its 10-year plan to end chronic homelessness in 2005, it had about 3,000 people who lived full time on the streets. Today, Salt Lake has about 400, according to a report in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Isn't it expensive to house homeless people? It is, said Somers, and it's not realistic to do it for everyone, only targeted populations. Canada's massive, five-city project required a $110 million investment from the federal government; Salt Lake's required $20 million and matching funds from charities and donors.

Still, it is often cheaper than leaving people on the streets. Homelessness in Canada effects 200,000 people a year and costs a whopping $7 billion in shelter costs, low enforcement and incarceration and ambulance rides and emergency services, according to the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness. The Canada study claims that every $10 invested in the housing first program has saved $22. Salt Lake estimates that each chronically homeless person costs the city $61,000, a year compared to just $16,000 a year to place them in supportive housing.

In May, the Central Florida Commission on Homelessness found that the region spends $31,000 a year per homeless person due to the salaries of law enforcement officers for arrests and transport of the homeless, mostly for petty offenses like intoxication or sleeping in public parks, plus jail time and E.R. visits for medical and psychiatric services.

Choice and accountability

In the At Home/Chez Soi program, participants look at two or three different apartments, in ordinary private market buildings where the program has negotiated with the landlord, and chose the one that they liked best. Then they worked with a case worker to choose a form of treatment for substance abuse, mental health issues or life skills, like budgeting, and case workers met with them at their homes at least once a week, sometimes more depending on need. Participants pay for 30 percent of their rent — the rest is subsidized through the program.

Receiving support at home, as opposed to a community or outreach center, is different, said Hume. Case workers can "be more respectful and engage in a way that's deeper when in people's homes," she said. It's also harder to hide problems at home — from drug abuse to hoarding.

Canada's program contrasts with programs like Salt Lake City's, where participants were placed together in new buildings designated just for program participants. The buildings are new and tasteful, with landscaped grounds. But Hume found that participants prefer to live in non-designated buildings where they can start to feel like "normal people" again.

"Neighbors are arguably the most potent element in intervention, and they don’t even know it. And they are a free benefit," said Somers, who notes that it can be difficult to feel integrated into society when you're in a building with only other formerly homeless people.

Participants in the At Home/Chez Soi program choose to move an average of two times over the two years. These are not evictions or calamities, said Somers, these are lifestyle choices. This population suffers from "systematic disempowerment," he said, from abuse to failure to stay in school or maintain friendships; they have been told from early on that they can't take care of themselves. Many didn't grow up with their birth families — 30 percent of the sample for the Vancouver study came from foster care.

"That comes with a high psychological cost," said Somers. Choosing housing is empowering, and choosing a place that suits you — good light, a neighborhood that you like, access to a job — are healthy choices that functional people make and can lead to more healthy choices.

The cost of helping the most vulnerable communities can be hard to understand if you're not reliant on public programs to get through key phases of life, said Somers.

"We tend to think that success is a matter of enduring hardships and following rules and getting things because you earn them, and we have to acknowledge that there is a small subgroup this doesn't work for." There's an economic argument for housing first, he said, but also a values one that requires us to "think about the worth of individuals."

Joe Hatch puts a finer point on it. He had attempted suicide more than 10 times before he was placed in housing. If he hadn't been chosen for housing first, or if he had been placed in the control group? "I would be in a hospital right now, or I would be dead," he said.

"We're not homeless people, we are just people who happen to be homeless," said Hatch. "People without homes have hopes and dreams and aspirations like everyone else. We're not just numbers."

Email: laneanderson@deseretnews.com