![]() Research proves still separate and still unequal

Research proves still separate and still unequal

In light of research released by the Department of Education, the Brown v. Board of Education ruling’s 60th anniversary Saturday proves less a cause for celebration as grounds for questioning remaining education inequities.

Brown v. Board was the historic ruling that declared “separate but equal” not only an impossibility, but unconstitutional. The National Education Association is using the occasion to point out that American public education is still separate and still unequal.

The NEA and the Journey for Justice rallied in Washington on Tuesday. The rally was called the Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools and was lead by Ocynthia Williams, a parent-leader with a New York chapter of Journey for Justice.

“This nation has a history of denying students of color the equitable resources they need to succeed in school,” Williams said to the press during the rally. “It’s been 60 years, and schools are still separate and unequal. They are more segregated than ever.”

Parents take to Capitol Hill

“Parents want to do what’s right for their kids,” Monica Silva, a Journey for Justice mom from New Orleans, said. “We know that it’s important for our kids to go to a good school. They need to learn math and how to read. They need to be prepared to go to college so they can get a good job. That’s how society works: No college means no money.”

But for low-income parents, especially those who are black or Latino, sending children to a good school is often impossible. According to the Department of Education’s research of all 97,000 of the country’s public schools, racial minorities are more than twice as likely to go to an underperforming, underqualified school than white children.

Another problem uncovered by the Department of Education is that a quarter of high schools with the highest percentage of black and Latino students do not offer any Algebra II courses, while a third of those schools do not have any chemistry classes — so the students with a natural aptitude for math and science are not given the opportunity to explore and develop those interests. This also harms the students’ chances to attain a university degree. When a high school struggles to maintain its accreditation, it loses its footing with colleges.

“I ask all the parents out there, what if your local school was bad? What would you do for your child?” Silva asked. “What if a fancy private school wasn’t an option? You’d be on Capitol Hill marching too.”

By class or by race, it proves the same

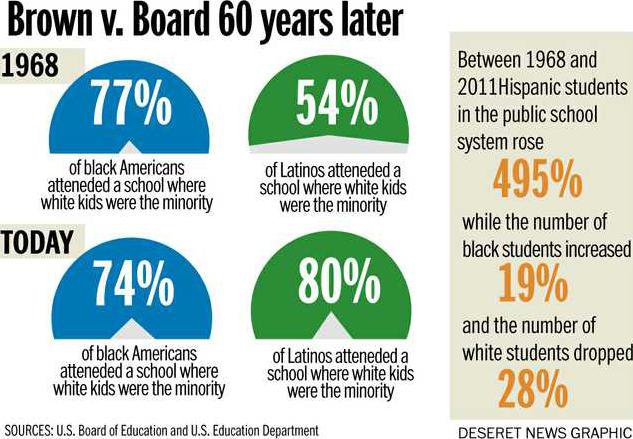

According to the U.S. Board of Education, 74 percent of black students and 80 percent of Latino students attend schools with white students making up 10 percent or less of the population. Though the district boundaries in question are made up predominately of racial minorities, the Department of Education reports that whites make up significantly more than 10 percent of the population.

“Most of the white kids in the these areas come from higher-income homes, so their parents pull them from the public school and place them in charter or private schools,” Dr. Pedro Noguera, a sociologist studying inner city schools in New York, said.

With the exodus of white students from struggling schools, the problems of public schools only worsen. Those left to support the community's schools typically have far less resources to do so. This unbalance between public and private schools was a main topic of protest at the rallies.

“Our schools have become high-stakes testing factories, and corporate America is trying to privatize them,” Williams said. “We say: no more. We are reclaiming our public schools, and we are demanding that the promise of Brown v. Board of Education be fulfilled.”

Many speakers at the May 13 demonstrations asked that all community members rally behind their local schools not break them down further by pulling support.

The 1954 desegregation ruling was followed by 30 years of slow integration, which was followed by another 30 years of steady resegregation along the lines of socioeconomics and race.

“Today in America, African-American children and Latino children are much more likely to attend segregated schools, and schools that segregate on bases of race and class, than they were in the 1970s,” Noguera said. “So the country without declaring an end has in effect started a process of retrenching and reverting back to segregated schooling.”

The subject is largely an uncomfortable one for legislators, Noguera explained, partly because the courts have put up new barriers and partly because no one wants to revisit the controversies of the past.

Lighting the fire of change

“We’re fighting a battle for our children that was legally won before we were born,” Angelica Smith, a parent-leader in Philadelphia’s Journey for Justice group, said. “Everyone would love if the problem had actually been fixed 60 years ago, but it wasn’t. Now is the time for our law makers to make it happen.”

Smith and the other Journey to Justice parents ask that all parents contact their state’s representatives, asking them to put equity education legislation into place.

“It’s time we lit a fire under them,” Smith said. “It’s time for America to become that promised land.”

EMAIL: nshepard@deseretnews.com TWITTER: @NicoleEShepard

60th anniversary of Brown v Board aims to light a fire

Latest

-

Its toxic: New study says blue light from tech devices can speed up blindness

Its toxic: New study says blue light from tech devices can speed up blindness -

This upset man was turned away from voting polls because he was wearing a MAGA hat; here's what th

This upset man was turned away from voting polls because he was wearing a MAGA hat; here's what th -

Facebooks stock suffers the worst single-day market loss in history. Heres how much Mark Zuckerber

Facebooks stock suffers the worst single-day market loss in history. Heres how much Mark Zuckerber -

Roseanne Barr speaks with Sean Hannity in first TV interview since racist tweet controversy. Here ar

Roseanne Barr speaks with Sean Hannity in first TV interview since racist tweet controversy. Here ar