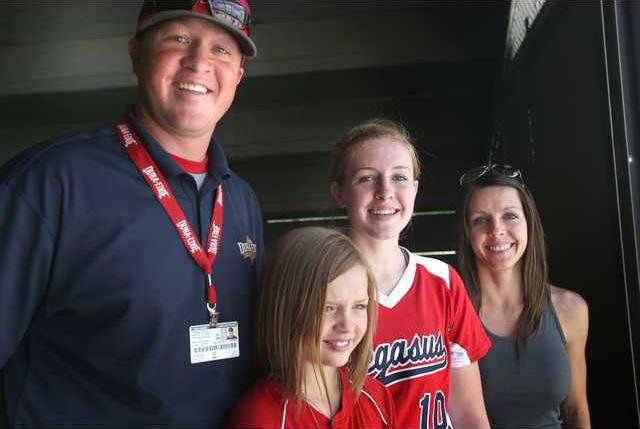

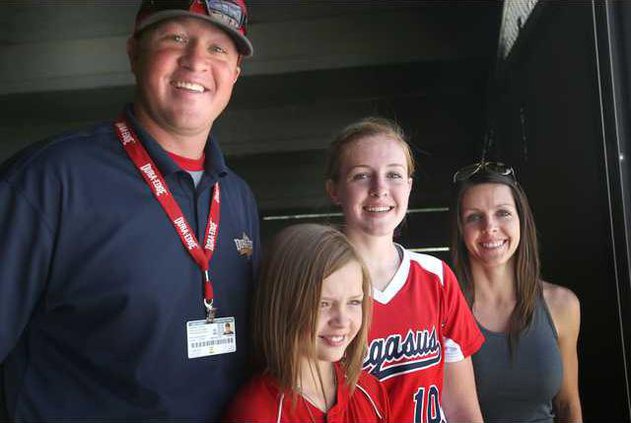

At ages 31 and 32, Katie and Cameron Toone are young compared to most parents of a teen. The couple got pregnant during high school. As soon as they realized it, they formed a tight family unit, every decision designed to help their family — their baby, now 14 — survive. They were focused on logistics, not yet knowing the physical and mental changes that would impact them both as they became parents.

While a man and a woman may each “expect” their first child, much more is understood about how a woman's body changes, from her burgeoning belly to hormonal shifts and new priorities. But men's bodies change in multiple ways, too, beginning at the time of the pregnancy and extending into parenthood.

Parenthood's impact on men and women creates “parental synergy,” according to a new report, “Mother Bodies, Father Bodies: How Parenthood Changes Us from the Inside Out.”

"Why is this the moment to share and reflect on these findings?" the report asks, then answers: "Today it is perhaps more confusing and more daunting than ever to be a parent. In recent decades, profound changes have upended accepted notions of mothering and fathering, providing new opportunities but also often leaving many new mothers and fathers feeling as though they must figure out how to do their parenting jobs largely on their own."

Changing hearts and parts

"What I love about this is that we approach this exploration looking at parenthood from the inside out, beginning with our bodies," said Dr. Kathleen Kovner Kline, a psychiatrist now affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania who co-wrote the report. "Part of our body is our brain. Hormones and neurochemicals that go through one go through the other."

The report sprang from an unusual collaboration between natural and social scientists at a 2008 conference at the University of Virginia, where participants shared research about pregnancy and parenting. The proceedings were published last year in a book, “Gender and Parenthood: Natural and Social Science Perspectives,” edited by W. Bradford Wilcox, director of the National Marriage Project at UVA, and Kline. They were principal investigators and wrote the "Bodies" report, released today.

It is a fresh way, she said, to look at a revolution that started in the 1960s centered on social roles — "who men and women are, what they are capable of and what they should be doing," she said, adding the researchers involved all know women can be chief executive officers and men can be good nurturers. Balancing responsibilities is the challenge.

The transition to parenthood occurs differently for men and women, with life focus shifting more for women, Wilcox said, as they veer toward motherhood and the child. The first child is a shock to a marriage in some ways, and couples can sometimes experience a shift in marital quality. Dad may feel left behind by Mom's focus on the baby.

Among women working full time, part time or at home, most want to work part time, according to surveys. “Not because we don’t love our work and not because we don’t love our children. They are two big, important jobs and we find value in both of them,” Kline said.

Men, on the other hand, change in many ways, but even as they begin to understand themselves as fathers, their worker identity doesn't change.

In the case of the Toones, who now live in Tremonton, Utah, Katie finished school and focused on her babies — Kapri, now 14, and Kinley, 10 — making her decisions through the lens of motherhood. When they first got pregnant, Cameron was a "big baseball player" but decided he needed to forego his season and "get busy earning a living to support my new family. My response was I had to grow up and take care of the decision we had made. I went to work, to school, came home, worked ’til 10 or 11 that night, then started over the next day."

Biology helps the identity shift into parenthood, particularly if the partners are game to let it occur, as the Toones were. Some chemical changes associated with bonding and affiliation increase when the couple are around each other, the report said, but the details are not well understood, though they know pheromones and other chemicals are involved.

Testosterone drops when a man becomes a dad. A father tends to work harder than childless peers and consequently earns more. He engages in an active way that seems to improve his life emotionally.

That's "one of the great things" that has happened in our culture in the family, Wilcox said. We expect more of men, of dads. The engaged-father model has important benefits for kids and men both.

Wilcox said the changes men experience when they are physically close to a mate and children lead them to be less aggressive and more interested in settling down. Their own biology primes them to be better caretakers in the wake of becoming dads. But those who don't live with their kids are less likely to enjoy these benefits of parenthood.

"The changes in the expectant dad seem to be mediated by contact with the expectant mom. He doesn't just automatically get it. It's being around her, mirroring, touching, hopefully in a positive relationship," Kline said.

Psychologist and zoologist Charles T. Snowdon found in mammalian fathers that both exposure to the mother and caring for offspring change animal dads in ways suggestive for human dads. They show hormone changes in males during a mate’s pregnancy, and among those who cared for previous offspring, changes occur earlier in pregnancy. Several studies credit animal mothers with enhanced boldness, food-finding ability and problem-solving after the birth — traits enhanced in nurturing males, too.

Even marmosets get the message. Cell structure changes in the brain of experienced marmoset dads, and the neuroreceptors for a hormone associated with affiliation increases. They become less distracted by single-girl marmosets.

Parenting today

In the natural sciences, an explosion of research describes the biochemistry of parenthood, but social scientists didn't recognize the science on the natural side, said David Blankenhorn, president of the Institute for American Values and co-host of the 2008 conference. Besides gathering both together to examine the "whole-parent experience," he said, conference sponsors wanted to get some distance from the “polarizations and simplicities that often accompany discussions of this, depending on where one stands on the conflict of the day. 'Everything is biology.' 'Nothing is biology.’ ”

Family life in America has changed. Couples delay marriage five years on average compared to 1970, and longer among the college-educated.

That's not the only difference between classes that increasingly divide along not just economic but educational lines, with the educated forming an upper class that is more traditional in terms of family life.

The story of those with less education includes more out-of-wedlock births, cohabitation and divorce. One study in the report said when women are less educated, about 42 percent of their oldest children spend part of their first decade in a family that is neither stable nor married. With college-educated moms, that's true for only 17 percent of oldest children.

Blankenhorn noted a “crisis of father absence and weakening of family structure among the 70 percent who are not upscale.”

Parenting is also both more intense and more costly, the report said. Parents spend 50 percent more time with their kids than did folks in 1975. The Department of Agriculture's annual reckoning says it costs the average family $226,920 to raise a child to age 18 — about $41,000 more than in 1960.

Still, the authors call parenthood "transformative" and "meaningful."

Intricate interactions

Blankenhorn likens parenthood to a pair of dancers engaged in a complex routine. It is hard for a mother alone or a father alone to provide a child with all he or she needs, he said, but when they are together, "the child tends to get the whole thing. Not everything is gendered, but a fair amount is."

He describes this scene: Junior and Jillie are running around a playground, laughing and trying new things. Mom yells, "Be careful." Dad says, "See if you can climb to the top."

The roles are not always that way, but research says it's a common pattern.

"The wonderful thing about that is that 'be careful' is a very, very fine piece of advice," said Blankenhorn. And 'can you climb to the top' is a very, very fine challenge. Both are pretty darned important and it's not like you have to choose which one is correct.

Together, they are great!"

Affection between partners brings chemicals that mediate feelings of reward. Touch, physical intimacy and verbal communication all trigger those chemical changes, said Kline.

“Of course, sex can be pleasurable and is requisite for reproduction. But this intense attraction to one another over time serves perhaps an even larger purpose. Blankenhorn notes it is the couple’s ongoing emotional entanglement and interest in one another that helps to create the couple that will raise the child,” the report said.

The father

Recent research has put a lot of emphasis on fathers. They aren't more important than mothers, said Blankenhorn, but they are less likely to live with their children. As many as 40 percent of kids go to sleep in a home where their father doesn’t live. Blankenhorn calls it “arguably our most urgent social problem.”

Wilcox is taken with the “generative power of fatherhood for men, in the biological, emotional and social sense. Men who live in close proximity to their kids and engage intellectually, emotionally, socially and athletically see their children flourish,” he said.

“Fatherhood is transformative for men.”

Because couples are different, they will do things differently, the report said. "Attention, affection and discipline are similar but they engage kids differently.

"There is significant variety in the range of adaptations married couples choose in work and family decisions," the authors said. "Families benefit when women and men are able to approach motherhood and fatherhood in the ways that best suit themselves and their mates."

Email: lois@deseretnews.com, Twitter: Loisco