Springfield, Ga. — When Tracy Oglesby Smith was growing up in Effingham County, her grandfather, George Langwood Oglesby, was simply “Papa George.” He was a quiet, hardworking man who loved fishing, tending bees and teaching his grandchildren how to drive a nail straight.

“He was really close to all of his grandchildren,” she said. “He was hardworking. He provided for his family. He was a man of few words, but you knew what he meant when he said it. He was really a wonderful grandfather.”

But he also carried a secret — one that tied a small-town Effingham family to the Manhattan Project, the United States’ top-secret World War II mission of the 1940s to build an atomic bomb. The man she knew as a farmer, builder and churchgoing patriarch had quietly helped shape the dawn of the atomic age. Decades later, after her father, George Langwood Jr., died, Smith began piecing together her grandfather’s past, determined to uncover how his hidden role placed her family at the center of a world-changing moment.

“I just felt it’s important to tell this story,” Smith, who now lives in Springfield, said, “or it would be lost forever.”

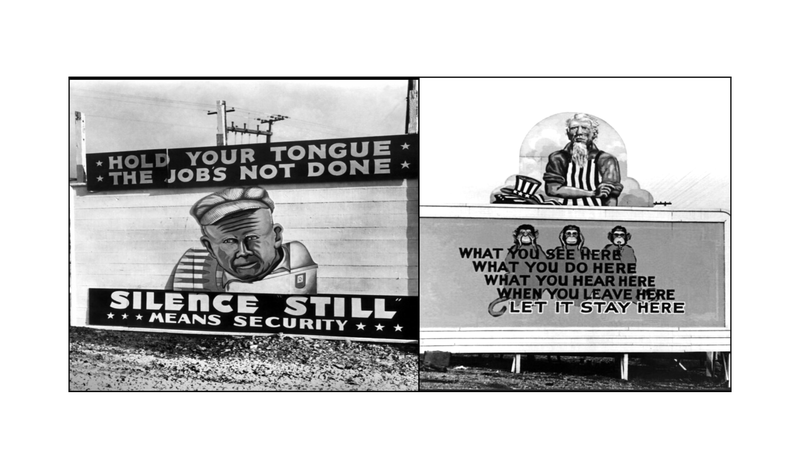

A Job Cloaked in Secrecy

In the early 1940s, Oglesby was working for A.C. Samford Construction Co. in Montgomery, Alabama, when he was offered a new position with J.A. Jones Construction Co. The job was in Oak Ridge, Tennessee — a place most Americans had never heard of.

What Oglesby didn’t know was that Oak Ridge was a city that technically didn’t exist. Hastily built in rural Tennessee, it was one of three key sites of the Manhattan Project — the top-secret effort to develop the atomic bomb, famously dramatized in the movie "Oppenheimer."

Before he could take the job, the government had to clear him.

“They had to send all these agents to our little, small hometown of Rincon and interview all these people,” Smith said. “Of course, nobody could know what was going on, or why the FBI was doing a background check on him.”

Oglesby accepted the assignment and moved his wife and four children — one of them, Smith’s father, just 5 years old — to Oak Ridge. There, he served as a general superintendent with J.A. Jones, overseeing work on the K-25 and K-27 plants. These massive facilities were part of the effort to produce enriched uranium for the atomic bomb.

K-25, completed in 1945, was the largest building in the world under one roof at the time. Oglesby was the building supervisor. Tens of thousands of workers labored inside and around its gates, most of them never told the full scope of what they were building.

Rumors and a Stone House

Back home in Effingham County, the sudden disappearance of Oglesby and his family fueled wild speculation.

“Rumors were going around that he had been in prison,” Smith said.

Besides a few close relatives he confided in, nobody knew what had happened to the Oglesby family — and those who did weren’t allowed to say a word.

The mystery deepened when Oglesby began shipping heavy loads of Crab Orchard stone from Tennessee back to Effingham by train.

“People also thought he was smuggling stones in, and maybe that’s why he was in prison and all this kind of crazy stuff,” Smith said.

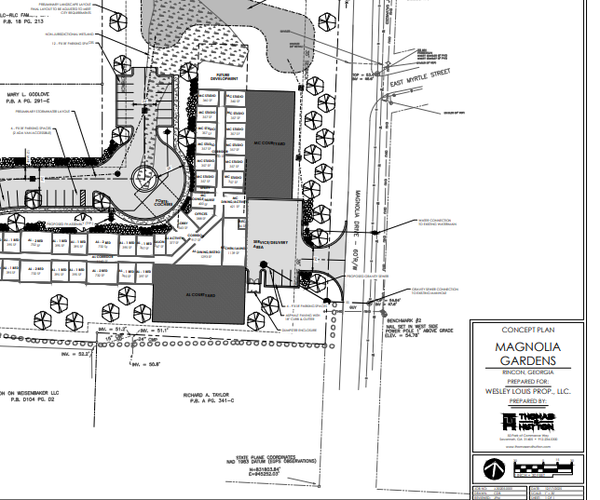

In reality, he was building what became one of Rincon’s landmark homes — a large stone house that still stands off Highway 21. The house at Highway 21 and Wisenbaker Road is now Mirror Image Hair Salon.

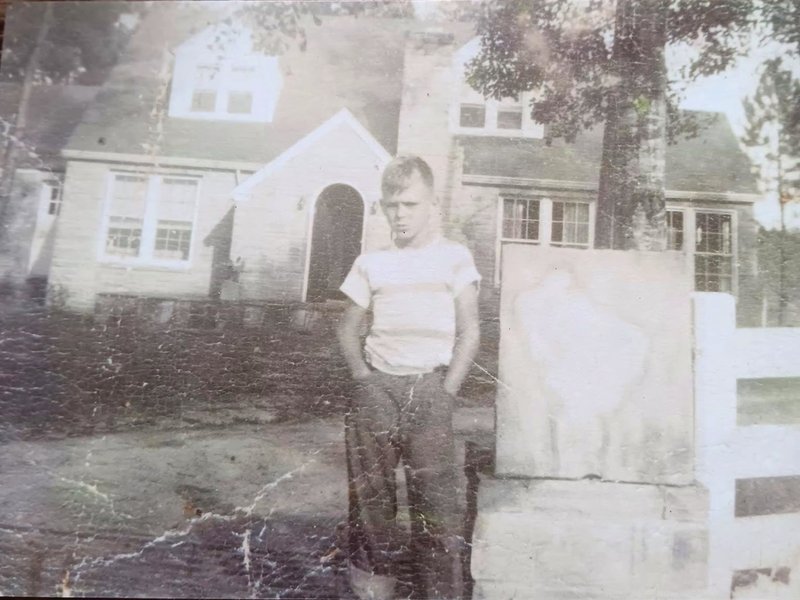

Childhood in a Secret City

Smith’s father, Langwood Jr., was old enough to remember flashes of Oak Ridge life.

“My daddy remembers being there outside of the gate, playing with the other kids because they couldn’t go in,” Smith recalled.

Even the children had to wear badges.

Her aunt, Martha, just 18 at the time, joined them as well.

“My granddaddy was one of 11 children — that was his baby sister,” Smith said. “He got her a job there as a secretary in one of the machine shops.”

It was only through her father’s recollections of those years that Smith learned of her granddaddy’s connection to Little Boy and Fat Man — the nicknames given to the first and only two atomic bombs ever used in combat.

Recognition, at Last

After her father’s death, Smith began digging for records — photographs, phone books, commemorative items. She had long known of a photo showing her grandfather at the Oak Ridge job site alongside executives, and of a commemorative piece shaped like a missile, but she wanted more details.

“My daddy was the only one that my grandfather talked to about this,” she said. “Daddy was very proud of what his daddy did. When he died, I wanted to be sure Papa George got the recognition that he deserved for what he did for the war effort.”

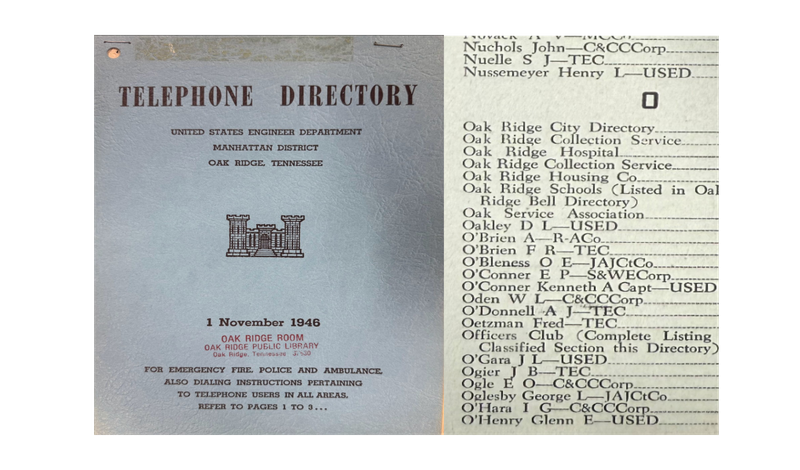

She enlisted the help of Mike Stallo, a historian in Oak Ridge.

“What I found was his name in a couple of phone books,” Stallo said. “That revealed who he worked for, which was the JA Jones Construction Co., which built the K-25 building among other buildings. And that he was relatively high up.”

Stallo explained that with 70,000 to 80,000 people working at the largest of the three Manhattan Project sites, only the more important names would appear in the phone book.

“He also had a residential phone, which was a little bit of greater status,” he said.

'He Was Part of History'

Despite his position of responsibility, Oglesby rarely spoke of his work in Oak Ridge.

“It was so secretive, some of his own family members never even knew,” Smith said. “Even decades later, he never really told anybody where he had been or what he had done.”

When the war ended, Oglesby brought his family back to Rincon. Life resumed in the small town. He worked construction jobs across the country, raised bees, went fishing and tended to his pond and garden.

According to his son Dale Oglesby, he lived as a man rooted in faith and family — never seeking recognition for his wartime service.

“I just want people to know he was a part of history,” Smith said. “It was a sacrifice for him and for his family. He went not knowing what he was going to do, and he did it in complete secrecy.”